Back in the summer of 2023, I had been pouring through the Early English Books Online database (as one does), and came across William Salmon’s Polygraphice (1673)— within which I found the following:

VI. To rectifie the Breath, when it smells of any thing that is eaten.

[…] by chewing troches of Gum Tragacanth perfumed with oil of Cinnamon.

Well, gosh, thought I. That seems very much like a note regarding a ye Olde Altoid. I wonder how hard it could be…

Cinnamon oil I felt confident about; I’d seen gum tragacanth in several recipes, so I had a passing familiarity with it; and garlicky breath apparently knows no barrier to time or space. I figured my first research step was finding out more about troches— starting with, uh, what they even were.

Troches (by any other name)

Troches (pronounced “trOh-keys” in American English and “trOh-sh-ez” in British English) are one of those fascinating bits of apothecary that have survived into modern times with a very similar meaning and usage. Merriam-Webster just calls them lozenges; compounding pharmacies seem to group them with sublingual (under the tongue or against the cheek) tablets. Mostly we use the term now to refer to individually compounded medicines, and separate out the more candy-like ones (or ones that have ingredients that we now just think of as flavoring, with no real medicinal effect) into categories like pastilles, mints, and some gummy candies.

My whole deal, though, is trying to figure out this stuff using only books and such from the 1710s or earlier, so when I came across this barely-a-recipe I fired up the ol’ databases and started digging. And while it’s still ongoing, I can say that getting descriptions and common ingredients (…and spellings) was pretty easy, and revealed some potential relative-recipes:

| Names | Description | Compounding Ingredients | Source |

| troches | n/a, why bother having a description, ahahaha | gum tragacanth, sugar | Barbette’s Thesaurus Chirurgiae (1687) |

| troches, placentulae, little cakes | “usually little round flat Cakes, or you may make them square”; “easier carried in the Pockets […] in a Paper” | mastic gum, gum arabic, any distilled water, gum tragacanth | Culpeper’s The English Physition (1652) |

| trochisks, troquisks, pastils, rolls, cakes, lozenges, sief, collyrium | “a dry Composition”; “small Cakes, to which you may give what Figure you please […] flat, round, triangular, square, long or otherwise”; more “solid” in mass than pills | gum tragacanth, rosewater | Charas’s The Royal Pharmacopœea (1678) |

| pastils | “flat […] of what shape you will” | sugar, orange-flower water, gum tragacanth | Barbe’s The French Perfumer (1696) |

| past, plate, comfits | “roul [roll] it very thin”; “print it in moulds of what fashion you please”; “cut it into small diamond pieces”; “dry” | sugar, gum tragacanth, rosewater | Woolley’s The Accomplish’d Lady’s Delight (1675) |

Table 1. Are there more resources out there? Of course. Had I found them by this point? Nuh uh.

(Of random interest, my bae Charas separates troches from tablets, unlike our modern-day definitions; he indicates that tablets use sugar as the main compounding ingredient to bind everything together, whereas troches already have gum tragacanth and therefore don’t need sugar. He actually groups tablets with “looches,” a honey-like throat/cough syrup, entirely because of the whole “sugar” thing.)

Getting back on topic, though, Charas identifies edible pastils as being “invented for Perfumes”, which is where Barbe comes in with his “Pastils Perfumed good to eat“— all other mentions he makes of pastils refer to perfumed incense. Usefully, though, gum tragacanth (or “Gum-Adragant”, as he calls it) and distilled waters like rosewater and orange-blossom water again appear as important compounding ingredients regardless of the end-use, so I took note of any instructions he cared to give on the topic.

And while it doesn’t look like Hannah Woolley’s food recipes should be in the same camp, one of Barbe’s describes how to “dissolve Gum to make the Paste for Pastils”– which gets us to Woolley’s “past” (paste) recipes, and the very familiar descriptions and compounding ingredients there. Culpeper, meanwhile, throws everything into the pot just in case, and Barbette wonders why you’re bothering him.

So by pulling up all these different references and recipes, I was pretty sure I could expand the ingredients list for a version 1.0 of Salmon’s breath freshener from his original bare-bones one (gum tragacanth and cinnamon oil) to something a little more robust:

- gum tragacanth

- distilled water

- sugar

- cinnamon oil

Yay! Now I just had to find a set of directions for making it!

Figure 1. Portrait of the apothecary waiting for a clear technical text to miraculously appear.

Time to Fold in the Cheese

I’ve mentioned the perils of “fold in the cheese” recipes before when dealing with the lack of practical, physical instruction into how to make something. “Fold in the cheese” directions are ones that use particular-action terminology without explaining what those terms mean (because it was explained in another text that I don’t have, or because the text is for trained experts, or because This Is So Common I Don’t Have To Explain It!)— or, worse, they’re not even intended to be directions, because the writer is just telling you a variant of something that you, of course, already have your own background knowledge of.

(To demonstrate why this is a problem, imagine someone in the distant future trying to figure out how to make a particular historical treat based only on a random line from some extant music that refers to “Mr. Pibbs and Red Vines equals crazy delicious” and nothing else.)

In the case of our troches, here are some examples of “fold in the cheese” directions given:

- “according to Art”

(Barbette, the least helpful because I think he’s busy writing just for other surgeons) - “with a little pains taking”

(Culpeper, who uses this to cover going from “jelly” to a “paste” that can be easily rolled out) - “being incorporated with some liquor, are made into a mass, of which are form’d certain small Cakes”

(Charas, who sounds like he’s giving good directions until you actually try it and realize “incoporate”, “some”, “made into”, “mass”, “form’d”, and “certain” could mean a whole lot of different things) - “a handful of Gum of Adragant”

(Barbe, who leaving aside the whole “hand” measurement thing, doesn’t clarify whether he means whole lumps of gum tragacanth or powdered, and believe me, there’s a difference) - “steeped”

(Woolley, who uses such a wildly unlikely word for what to do with the gum tragacanth and the rosewater that I begin to doubt her stuff belongs at all— unless—)

Unless...

Part of why finding all the relatives and odd off-shoots of these recipes is important is that any one of them might end up providing one or more crucial details not present elsewhere. Woolley using the word “steep” to describe how to prepare the gum tragacanth may actually be a relevant and useful term (overlooked by the male writers!). And I know that Barbe, though he doesn’t appear to have any other extant works (UNFORTUNATELY), is generally one of the better instruction/technical writers I’ve come across– it may actually mean something that he didn’t say anything about powdering the gum first.

So with this in mind, reconstructing the directions for one of these recipes begins by making a note of all the variations I could find, and then testing them one by one to see what happens. Salmon’s recipe, having a grand total of no directions at all, meant that my version 1.0 was going to be, shall we say, an Adventure— but I was pretty confident about my first step, which was:

- Make a mucilage out of—

Figure 2. Just imagine a record scratch here, this isn’t MySpace, we’re above embedding sound effects.

Mucilages for Fun and Profit

(Yes, it is pronounced very much like “mucus” and yes, you will find out how relevant that is.)

Tangent time! This is gum tragacanth:

It’s pretty cool stuff: it can bind without being sticky like gum arabic; it’s flavorless and malleable so can be used to create edible floral sugarcraft the way fondant does; it can be used to burnish leather; it can be the adhesive on rolled cigars; it can be turned into a summer drink. Over time, cheaper, easier to source, and sometimes artificial ingredients have replaced gum tragacanth in areas where it used to reign supreme.

Way back in the Early Modern era, though, that wasn’t yet the case, and gum tragacanth was a key binding agent in a lot of stuff. So learning about how to prepare it? Definitely important. But directions for preparing it are… not easy to find. The only technical term I could find for the preparation was “mucilage,” a medical/apothecary term used by Charas and Culpeper— everyone else just kind of used shorthand for what they expected you to do (e.g., “dissolved” and “steeped”), because by the late 1600s it seems like everyone who knew to use it also already knew how to prepare it.

Which maybe I could eventually overcome if there was one standard way to prepare a mucilage— I would just need to go far enough back to find someone describing it (like I had once upon a time with “sallet oyl”)— but, uh, nope. Of our sources here, it seemed everyone delighted in having at least one, but preferably more, completely different methods for making a mucilage:

“At night when you go to bed, take two drams of fine Gum Tragacanth, put it into a Gally-pot, and put half a quarter of a pint of any distilled Water fitting the purpose you would make your Troches for, to it, cover it, and the next morning you shall find it in such a Jelly as Physitians call Mussilage” (Culpeper)

“[H]aving finely powder’d the Ingredients which are to be powder’d, they are to be incorporated with some juice, syrup, or other viscous Liquor, to make thereof a solid paste” (Charas)

“[D]ip in Orange-flower-water a handful of Gum of Adragant, from Night till the next Morning: strain it hard through a Linnen Cloth, not too Fine nor too Coarse” for edible pastils; for all others, “[d]issolve your Gum in what sort of Water you please, but the Water must not be over it above an Inch, because you must not drown it presently; and when it has soakt in the Water, pour some more fresh, and so by degrees till your Gum is dissolved; it must not be too liquid, but softish and well melted, then use it.” (Barbe)

And in writing this post, I literally just now discovered that Charas— NOT in his chapter specifically about troches— gives another set of directions, saying:

“[P]ulverize two drams of Gum-Tragacanth very white, and infuse it upon hot Embers in five or six ounces of good Rose-water till it be altogether dissolv’d and reduc’d into a thick but soft Mucilage”—

Figure 4. Oh cool I did not know heating was an option, I will be Responsible with this knowledge.

And like. If the outcomes were different, I would assume that maybe different consistencies of mucilage were important and therefore there might be more than one recipe. But again: NOPE. The outcome is supposed to be a paste you can roll out and then cut into shapes, either with a knife or a mold, and then you dry them. EVERY TIME.

…and it was at this point in my research, dear Reader, that I perhaps went a touch Mad.

Cinnamon Troches, Version 1.0

Shortly after discovering Salmon’s recipe, and not yet having discovered the gond katira form of gum tragacanth, I bought myself a powdered form for sugarcraft that I very much hoped wasn’t stuffed with additives. Why so soon? Because I wanted to be prepared to start once I felt confident enough to try a full recipe. Come mid-September, though, I lost the battle with “patience” and also “reasonable research”, and I decided the time had come to just give it a go. Surely I had found enough references to understand what I was doing. Surely it was just a straightforward “put gum in water, wait, take out the jelly, beat until paste”— right?

Surely.

Figure 5. An extremely cheap joke.

I pulled out the powder, readied a bottle of water (because Culpeper had said “distilled water” and I hadn’t yet cottoned on to its more exact meanings), and with no clear idea of what the heck would come out the other side, I set myself to trying to make a mucilage.

Up to that point in my rambling apothecary journey, I’d preferred writing up my adventures after I’d either learned something fascinating or had time to see the end result of whatever I’d attempted. But, as I said, a Madness had come upon me and— because I was perhaps Too Easily Amused at the notion of horrifying my readers— I started posting in-progress notes sans any actual indication of what I was actually, like, doing.

So keeping in mind that you have significantly more information now than those readers did then:

10:32 PM, September 14, 2023

live from the workshop

Figure 6. A strange, poorly measured powder (because I had neither teaspoons nor fucking drams at my disposal)

Figure 7. Oh no.

Figure 8. Oh no.

Tomorrow I must return to it and see what time, and my own Terrible Choices, has wrought.

7:41 AM, September 15, 2023

[In response to a reader commenting on the “Oh no” caption:]

What’s great is that it’s literally what I said out loud as it was happening.

And then, as I kept stirring and it kept being Like That, I started to laugh in continued gleeful horror, thereby suggesting that, in the course of my ongoing Science, I am perhaps evolving from one kind of narrative archetype to quite another.

…though I admit, as worrisome such a transformation might be, having an Igor around would be incredibly convenient.

11:09 PM

live from the workshop

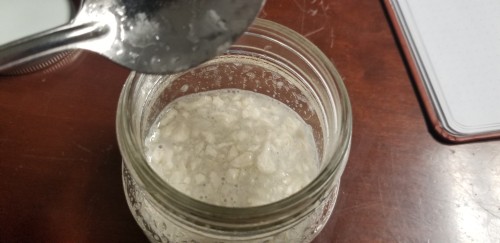

Figure 9. What would appear to be the strange, scentless lovechild of watery tapioca

and the contents of an old man’s handkerchief.

What 24 hours in a sealed jar has revealed.

And Reader, I need you to know that I did

with malice aforethought

put this mixture in my mouth.

For science.

6:42 PM, September 17, 2023

live from the workshop

Figure 10. Goo. On finger.

…I put it in my mouth again.

9:43 PM

[In response to a reader asking in very excited tones and many all-caps why I was putting this unknown (to them) substance in my mouth:]

The scientific revolution depended on the acceptance of empirical evidence over Galenic theory! That makes putting weird stuff in my mouth practically a requirement!

[In response to another reader who pointed out the unfortunate similarity the substance had to other bodily excretions:]

INCORRECT it is mystery ingredient [redacted strikethrough] [redacted strikethrough] [redacted strikethrough]

… mucilage.

MUCH MORE NORMAL

7:35 AM, September 18, 2023

[In response to yet another reader wondering about my life expectancy vis-à-vis my new-found love of eating mysterious apothecary mixtures:]

I mean, to be fair, it’s only a mystery substance to you all.

I, however, am completely almost entirely at least 90% 80% 65% confident that this ingredient is totally safe to ingest!

And! Unlike some historical ingredients, this one is still in use in modern times!

for burnishing leather, mostly

See? TOTALLY FINE.

6:42 PM, September 24, 2023

So I sort of left the Mystery Project for a few six days, just to ensure that it would totally dry the way it was supposed to and—

Figure 11. Motherfucker.

After a pause to review modern directions (which hilariously are JUST AS FUCKING USELESS as the 1600s one), I proceeded to beat the shit out of the mix for a looooong time, because that would definitely lead it to solidifying—

Figure 12. God damn it.

Finally, I took the mix home from my workshop so I could add more of an ingredient I only have (for now) in my kitchen.

And while I’ve taken a brief break for dinner, please behold:

Figure 13. Astonishing frosting-like goo?

…for the record: I put it in my mouth. Again.

AND I GOT SOMEONE ELSE TO TASTE IT TOO.

And Returning to the Narrative in Progress

I never got the gum to solidify more than that, even when I added significantly more sugar (the mystery ingredient I reference in my kitchen). My sister was the one I got to try it, thus proving that I should not be allowed to have house parties. The flavor, pre-sugar, really did taste of basically nothing; when I was still in the workshop, I added cinnamon oil, upon which it, well, tasted like cinnamon; and when I added sugar, it did, in fact, taste like very sweet cinnamon.

So, being unable to do anything with it and with no immediate use for it, I tossed it… and then didn’t attempt a 2.0 version

for

nearly

a

YEAR.

Figure 14. And welp, there it is: a cliffhanger.

Discover more from Katherine Crighton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply