Or, in the common parlance: Here’s how the IndieCade-nominated, live-action, cozy, not-an-escape-room location-based experience Memoirscape managed to host a full, remote playthrough for an international audience of players— along with some stuff we learned along the way, and how these digital runs could open the door for remote players AND provide an accessible/sensory-friendly option for audiences who may have been locked out of this kind of live experience before now.

Figure 1. Behold! An escape room (for some very very specific definitions of “escape” and also “room”).

1. A Brief Bit of History for the Edification of the Young

So way back in the humble Spring of 2024, I was part of the team of students in WPI’s Interactive Media & Game Development program that created an escape-room-ish experience called Memoirscape that would go on to appear at Foundations of Digital Games 2024 and then further go on to become a nominated game at IndieCade ’24. (And if you want to dig further into all that, more information can be found on my portfolio page and a truly ridiculous amount of History and Feelings can be found on my blog here and here.)

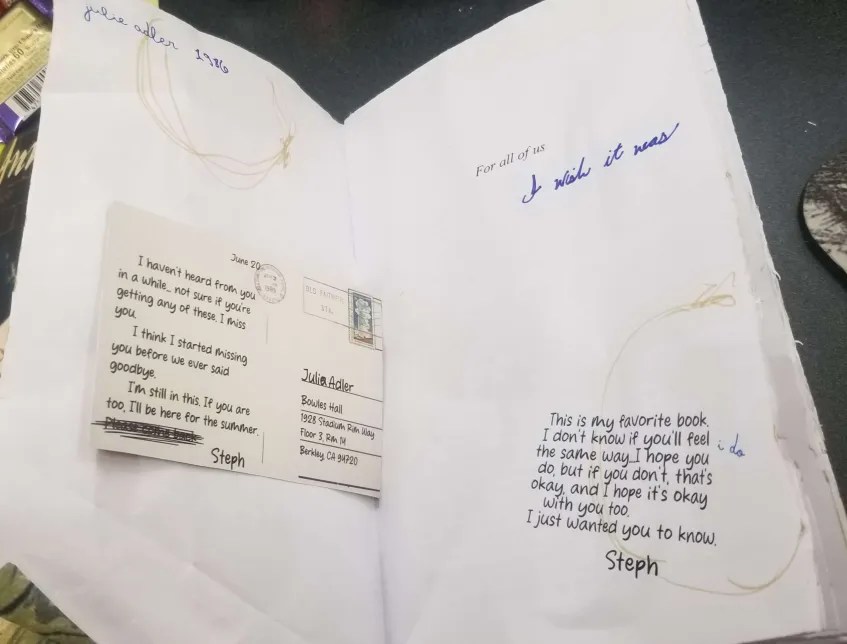

Starting in mid-April or so I fell into the jaws of a creative fugue state, developing paper ephemera for Memoirscape to increase the immersive elements of the room(s) and to boost the narrative/internal-timeline for audiences. With the impending doom deadline of the room’s public opening, I was spending every spare waking moment I had with scissors and Glue Dots and invisible ink— including April 25th, the night I attended a monthly cocktail Zoom party co-run by the editor and one of the hosts of The Cryptid Factor (a podcast slightly about weird news and mostly about three friends having a nice time trying to make each other giggle). During the course of this Zoom party I ended up waving my work around like a madman in lieu of actually having a drink, and everyone was exceedingly kind about it.

Figure 2. It was a wild time. Ignore the chocolate wrappers.

After the room actually opened to the public, I extended an invite to the cocktail team (because Such Is The Way when one wishes to apologize for screeching about The Immersive Importance of Tea Rings at someone else’s party)— but as they reside in New Zealand I did not particularly anticipate an acceptance. Imagine my surprise, then, when TCF’s editor, Halina Brooke, asked if it would be possible to do a walk-through recording for her… and I realized that, in fact, it might be possible to do a live, first-person remote playthrough.

Somehow.

2. And, Well, This Is How

Let’s skip ahead and forward and sideways around the testing and permissions and timing to get to the actual meat and potatoes of running this (though incredibly massive shout-out to immersive-narrative fan and Sleep-No-More pusher Michelle Paul for beta-testing the audience side of things on very short notice, huzzah)—

The bare-bones elements for a remote playthrough of a location-based experience

Required

- A minimum of 3 crewmembers

- A Zoom room on a paid account (so that it won’t shut down after an hour)

- At least one working smartphone with consistent internet coverage throughout the entire gamespace

Optional but Extremely Nice

- A smartphone camera cage with neck strap (something similar to this)

- A list of non-sequential shortcut links to important narrative materials— such as audio (both as sound files and as transcribed documents), art (in close-up if required), and text— saved to separate folders

Let’s dig into each of these in more detail (and with spoilers, if you care about that sort of thing).

a. A minimum of 3 crewmembers

This is the thing I think might trip most people up when it comes to “how” to pull off a remote run.

To be clear, in a regular, on-location play of Memoirscape, there was a minimum of 2 actors on-site required (though 3 were preferred, and that doesn’t even count the server full of backup folks to handle emergency tech problems):

- The Teaching Assistant (TA), who welcomed players, took their ticket payment, gave the safety rules and introduction to the game, and let the players into the official gamespace: the “Memoirscape demo”. The TA stayed outside the demo, though could come in and answer questions or reset elements as required.

- The Admin, who stayed inside the demo to provide assistance, answer questions, give clues, reset elements, and generally reward or encourage players to maintain the “cozy” experience. However, if necessary, the TA could take on the Admin’s role.

- Professor Adler, the “creator” of the demo. She was on an entirely different floor than the demo, in her very real faculty office in our very real college building. She couldn’t leave her office until the end of the day’s run, as her existence was not something that every player was guaranteed to discover.

With the remote run, we had originally planned to have multiple actors on-location, but the timing was rough and our luck was wonky, leading us to discover the minimum required number of 3 crew:

- The Host, who runs the Zoom room. They welcome players and give any content tags or safety rules that might apply. They also moderate between the remote players and the on-site crew, passing along questions and being the deciding vote if there are multiple requested actions.

- The First-Person Viewpoint (FPV), who wears the camera cage and serves as the players’ on-location “body”, moving around, looking at things as directed by the Host/players, and describing sensory elements the players otherwise can’t (such as the smell of a cologne, the feel of a couch, the taste of tea, etc.). The FPV also serves the same role as the Admin in terms of answering questions and rewarding/encouraging players; since you never see them directly, they can seem like an inner-voice or narrator for the players. (Though put a pin in that.)

- The Acting Crew (AC), who perform(s) every non-player character role, serves as the FPV’s on-camera “hands”, and generally acts as a handler for the FPV.

Again, that’s the minimum–but it’s possible. Crucially, though, each of these roles requires skillsets and rehearsals that don’t completely overlap with the regular on-location actors.

Recommended remote-play crew skills and rehearsals

The Host

- run and maintain the security of a Zoom room

- moderate between the players and the FPV, casting tiebreaker decisions as necessary

- keep the players tuned in to the gameplay and engaging with the narrative

- provide a template for interaction and play for those who are unfamiliar with collaborative Zoom events and/or immersive experiences

The First-Person Viewpoint

- carry the camera (sometimes for hours)

- frame the view for the Host and players in such a way as to maintain illusions and nudge clues

- move the camera steadily and slowly to prevent poor transmission and nauseated players

- be prepared to provide sensory information if requested (or to volunteer it if the gameplay warrants doing so)

- trust the AC with physically directing them and keeping them safe

The Acting Crew

- know and be prepared to perform the physical choreography required for the storyline (e.g., what props will need to be manipulated, what doors will need to be opened/closed) that the FPV can’t

- keep an eye on the FPV’s/players’ camera view so as to stay out of frame when just providing physical guidance

- keep an eye on the FPV’s/players’ camera view when required to act as the FPV’s on-camera hands or feet to help maintain visual continuity and bolster the illusion

- be prepared to play on-screen characters that talk to the camera’s “eye” rather than the FPV’s

- nonverbally direct the FPV to safely move them through the environment

- maintain emergency supplies (e.g., spare batteries, water, etc.)

To be honest, if you’re considering a remote play, hopefully you’ve already got somebody on your roster who can Host. In the case of Memoirscape, Halina was given the bare outline of the overall narrative and its solutions so she could keep the players on track, but otherwise we relied entirely on her practical experience in handling a highly interactive Zoom room. (And if you have questions about how she manages that, her inbox is ready for your queries.)

I would recommend that either the FPV or the AC (or, preferably, both) be extremely familiar with the experience as a whole; they can both contribute significantly (directly and indirectly) to the overall mood, narrative tension, and action for the remote players. The FPV in particular is a literal proxy for what would otherwise be the players’ embodied experience; knowing what’s significant and how to frame it for the players is an important element of a successful remote play.

Having multiple ACs is preferable, but it can be managed with just one. (I know, because we did.) But! Nota bene:

- We were able to fall back on just one AC because the “handler” AC I’d brought on was my sister–and not only did she come on board with stage experience and background knowledge about Memoirscape, but we already had a trusting creative relationship that allowed us to shortcut a lot of the recommended rehearsals when disaster struck.

- Even then, though, I ended up “creating” two additional ACs in the form of really simple puppets to represent Myself (before and after the game) and an “Admin” (who could be called on for hints and assistance during it).

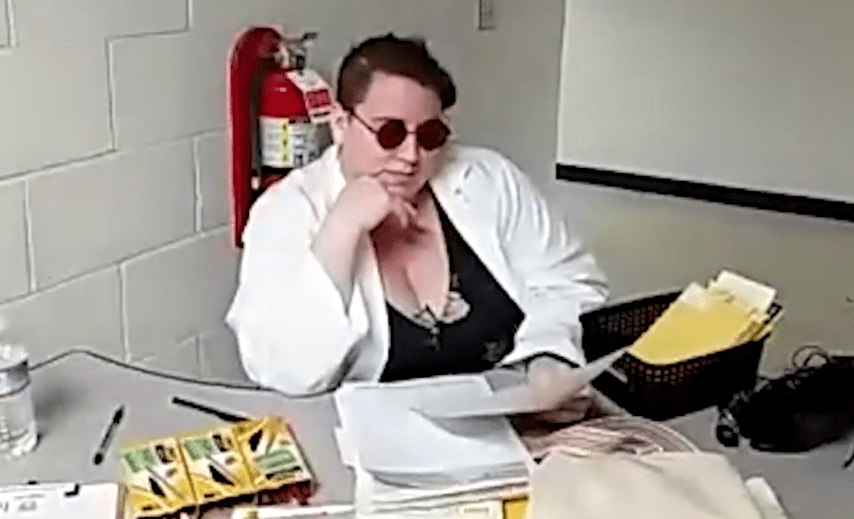

Figure 3 and 4. “Myself” on the left, as Halina and I discover that it’s somewhat disconcerting to coordinate face-to-wall.

On the right, a hastily raised “Admin” puppet, as I had been playing the FPV as a cheerful-but-clueless proxy for the players,

and suddenly we found that a helpful assist from the equivalent of Clippy was deeply necessary.

(Memory calibrator prop designed, built, and programmed by Cumhur Onat.)

You may also be wondering about the “FPV and AC both watch the camera as they move through the physical experience” thing. I’m not entirely sure how to explain it, but if you’ve ever seen Muppeteers coordinating a big production using television screens, it’s very very similar. This is absolutely something that benefits from rehearsal ahead of time.

Figure 5. Look, I don’t want to tell you how to live your life, but here’s the link to the

1981 TV documentary Of Muppets and Men,

please enjoy one of my deeply formative childhood experiences.

b. Zoom

For TCF’s digital run, Halina used a regular, paid-account Zoom room, during which we had about 30-odd players from several different countries (and multiple timezones) throughout the 2-hour play. The majority of the players were part of the regular community and so between the players and Halina there was an established culture of:

- generally staying muted unless specifically contributing

- extensively using the chat function

- Halina moderating between myself as the camera operator and the players in Zoom by staying unmuted but watching for “raised hand” reactions, reviewing the chat for commentary, narrating her experience, and regularly asking the group for feedback

Because that’s a bit of a unique situation, though, and I don’t think it would be wise to assume that all digital players will either (1) know each other, or (2) have experience in collaborative shenanigans, I would suggest that there might be value in testing remote runs with:

- a group in a Zoom room, but with a more extensive pre-room script between the Host and players to establish the dynamic and etiquette of digital play;

- a group in a Zoom room, but with some kind of worldbuilding mini-game (such as, in our case, perhaps a “machine calibration” to make sure our players “integrated” into the room correctly) that helps teach the players the best dynamic and etiquette for digital play;

- and (less preferably, I think) a group in a Zoom webinar— which locks down the players to only the chat unless the host lets them specifically speak— and then again exploring both of the above options

With regard to the actual setup: TCF typically runs the monthly cocktails in gallery view, interspersed with the hosts spotlighting different speakers to ensure that everyone can see them or their drink clearly. That wasn’t going to work for Memoirscape, though, since we wanted to keep as much immersion as possible despite working at the disadvantage of remote play. As such:

The order of Zoom setup and direction

- Create a Zoom room (either password-protected or otherwise private), set so that the Host lets participants in from a waiting room.

- The on-site “first-person viewpoint” (FPV) crewmember accesses Zoom via their smartphone, either already in the camera cage or with several dizzying seconds of video as it’s shoved into it.

- The Host lets in the FPV to test the sound (can the Host hear the FPV? can they hear the AC? can the FPV and AC hear the Host?) and the view (is the internet strong enough for a clear view? is text oriented correctly? are anyone’s fingers awkwardly on camera?).

- Spotlight the Host so they can welcome in the players and introduce the game.

- The Host transfers the spotlight to the FPV, such that the players’ screens and the FPV’s smartphone show just the gamespace— this way, the FPV can use the higher-resolution back camera to shoot video and use their phone screen (in Zoom) to frame exactly what the players are seeing.

- At the end of the experience, transfer the spotlight back to the Host (and/or a gallery-view) for the cool-down/post-mortem/aftercare of the players.

c. Smartphone

For our remote playthrough, our smartphone had to have the following capabilities:

- Front and back camera (preferably with a sufficiently high resolution on the back camera that writing in the game space could be clearly read without any unfortunate pixelation that might break the illusion of the players “seeing” the space for themselves— THOUGH people who are used to Zoom are used to a level of low resolution that may help fudge any deficiencies in this matter)

- A Zoom app (and phone itself, to be honest) updated well before the scheduled event to prevent unfortunate interruptions mid-play

- Sufficient working memory such that continuous Zoom video wouldn’t jump/lag/freeze for the players

- The ability to connect to the internet throughout the entire gamespace, via either very good wifi OR very strong signal (important for us since the majority of Memoirscape happened in a concrete subbasement)

For anyone concerned that this sounds complicated: We did this in 2024 using a geriatric 2008 Samsung Galaxy. You’ll probably be fine.

We originally planned for there to be two smartphones in play: the one in the camera cage, and another held by an AC. Both phones would be connected to Zoom, though the AC’s phone would be just another “player” in the group. Both the FPV and the AC would then have headphones in to minimize disturbance to others (important since Memoirscape was built in a working university building), though the AC would keep their Zoom muted to prevent an echo effect.

Upon arrival, though, and with minutes before we were due to start the remote play, the second phone couldn’t log into the university wifi and the subbasement-ness of it all prevented any sort of signal from getting through. Fortunately, it was after-hours and classes were over for the year, so we decided to live like fools and ran it sans headphones so everyone could hear the directions of the Host/players.

Important smartphone tips

- Always check your wifi/signal throughout the entire space

- Turn off alarms and notifications, particularly if they create an unfortunate buzzing sound (that’s very definitely audible over the Zoom)

- Keep a backup battery on hand and accessible throughout

- Set a reminder to update any/all apps that may be used during the course of play

d. Smartphone cage with strap

Onto the nice-to-haves. Do you definitely need a cage strapped to your neck? Maybe not. But here are the upsides to having one:

- It gave a steadier view than just holding the phone by hand, since it encouraged the FPV (me) to walk more slowly, keep pans slow and steady instead of swinging around like a loon, and not jump and jitter the camera up and down but rather move the entire body to “see” different things.

- By extending the cage to the end of the strap and choosing a comfortable arm position to carry the cage, the FPV could largely maintain a steady “viewpoint” height throughout the experience, again helping maintain the illusion of the players seeing through the FPV’s “eyes” rather than being continually reminded that someone was waving a phone around.

- With the two-handed grip, there was no danger of accidental thumbs and fingers getting into the shot– again, preserving that important “eyesight” illusion.

- I’ve seen some cages that strap to the chest, but having a cage that’s held away from the body ensures that the FPV and the AC can use the viewfinder together to see what the players are seeing, which becomes crucial when doing some of the more finicky viewpoint-illusions during the game.

Some things that were less useful, though, and that would probably benefit from more testing:

- Getting the camera in the cage was, in my case, a bit of a nightmare, since I had a third-party ring accessory glued to the back of it which very much interfered with any sort of balanced placement.

- Similarly, trying to use the touchscreen once it was in the cage and strapped to me was Not going to happen with anything like delicacy.

- The two-handed grip was great— until I needed to use it one-handed for any reason, at which point I apparently forgot how to hold a phone at all. (However! this did lead to me realizing the importance of a hand-actor AC, so you can decide whether or not you really want to consider this a downside.)

- Perhaps I would have chosen a different neckstrap for myself, if I had more time and/or felt like spending money. As the camera cage and strap were borrowed items from the college’s technology center, though, and therefore were the incredibly high price of free, I shall decline any further complaint.

Figure 6. Also definitely avoid mirrors (…unless it’s funny).

e. Important narrative materials available separately online

This one’s a little difficult to explain, but essentially:

- For each element that is necessary to progress the narrative or solve a puzzle in the gamespace, it’s really nice for one or more digital duplicates to be made available on a separate site that players can access on their own AND accessible only through non-sequential links (i.e., ones that do not progress numerically, such that a player can’t guess the next before organically discovering it).

- As an example, here’s the first link we had for TCF’s digital run: https://tinyurl.com/AdlerParticipantSurvey

- The links should only be released by a member of the game crew (Host or AC) as the elements are discovered in the gamespace. (The FPV absolutely does not have the hands available for that.)

The links themselves can be to individual elements, such as the one above, or it can lead to view-only folders (in our case, Google ones, but OneDrive or Dropbox would work as well, I suspect) with accessible variations on those elements— including but not limited to:

- audio: MP3; transcript

- art: JPG, GIF, or PDF; alt/descriptive text

- video: MP4; alt/descriptive text; transcript (if applicable)

The goal behind this one is to ensure that as many of the immersive, sensory elements of a game space as possible are available to the players despite being remote— and that neither the shortcomings of the Zoom connection nor the length of time spent by the Host on a location should prevent any player from getting to spend time and attention on elements of the story that they want to.

Why do I care about this? Well:

- Memoirscape was intended to be a cozy experience, so letting players spend however much time they wanted with an element (rather than rushing around trying to solve things as quickly as possible) was an important bit of theming.

- Similarly, while the on-location gamespace allowed players to disperse and interact with elements under their own direction (agency!), the FPV artificially forced a single direction for all the players; giving these links to the players, once they’d organically “discovered” them in the space, would allow them to choose to either follow the FPV or spend more time with the online element (and make that choice anytime they liked during the course of play!).

- The transcript option is actually something I would have loved to have available in the on-location game as well, but at the very least, providing the audio and the transcript outside the gamespace would provide a level of accessibility that otherwise might not be possible through Zoom.

- …To be honest, I was worried that the players would get bored with just the camera pointed at a tapeplayer for several minutes as they listened to a potentially unclear recording, so I wanted alternatives to a resting screen available. That ultimately was not the case with us, hooray, but it may be worth testing.

- And finally, it gives you the ability to add extra bits of information or interactivity if you want to get really wild— I could imagine some simple javascript games to help mimic the physical puzzles, and we did have a GIF of a postcard from the game that players could see more clearly— which, then, was available as an extremely handy backup when we ran out of the paper versions one night.

Figure 7. Theoretically, this is a GIF of a postcard that flips from a touristy photo of Yellowstone

to a thank-you and coupon for a free re-entrance to Memoirscape…

But it’s also possible that I forgot to set it to continuously flip,

so lord knows what you’re seeing right now.

So I stand by this one, but— it requires a wee bit more playtesting than we managed at the time. Our original plan was to have the AC drop the links into the Zoom chat, but the fail of the second phone’s internet scratched that. Our backup was to have the Host drop the links, but (to the game’s credit!) Halina was sufficiently immersed in the gameplay that we just kept on and let the players experience the elements through the camera.

3. How This All Worked (or Didn’t) on the Day

Okay, now you have an idea of the minimum requirements we found necessary to run a remote playthrough. But how did it actually work?

As I said before, I’m going to skip around the testing and permissions and timing and start with the day of. The AC for TCF’s run was a role taken on by my sister, Pippin Macdonald (the available member of the sibling No Story Is Sacred/M3C creative team I could get on short notice). I’d originally brought her onboard because the beta test with Michelle had demonstrated that sometimes I just needed the use of two hands, and at best I could manage one (and the camera would go all wonky every time I tried).

The solution we found, and that led to the creation of the AC in the first place, was Pippin staying off-camera until I needed something manipulated and then squishing up in such a way that her hands would appear to be my own. Not only did this help prevent awkward camera movements and fumbled props, but it also led to a surprise heightening of the illusion of the FPV’s camera being the “player”‘s viewpoint. The camera could stay steady even with both hands in shot.

Figure 8. A particularly successful example of the two-hand illusion,

where it appears that someone is looking down and picking up the playtest copy of Annie on My Mind.

In reality, the FPV is using both hands to angle the camera cage to “look” down,

and the AC has aligned themselves with the FPV to allow them to put a hand into the shot

at a natural angle. Both the FPV and the AC use the smartphone’s viewfinder to frame the illusion.

I’d brought Pippin in specifically because the timeline was extremely tight and didn’t allow for anything but the thinnest of run-throughs ahead of time, so I tapped someone who was essentially a familiar improv partner. We’ve worked together creatively long enough— and she has sufficient stage experience— that I felt confident we could largely coordinate without talking very much, could pick up one another’s cues, and that she would successfully direct my movements, open doors, and prevent me from falling over and breaking something.

But! On top of that, a series of unfortunate events led to us having no other ACs available on-location— and so we had to figure out how Pippin could be the FPV’s hands as well as the TA and Professor Adler. This, though, I consider the easier ask— all we needed were a couple of quick changes, specific entrances and exits, and remembering to cheat the camera one way or the other to keep her out of frame.

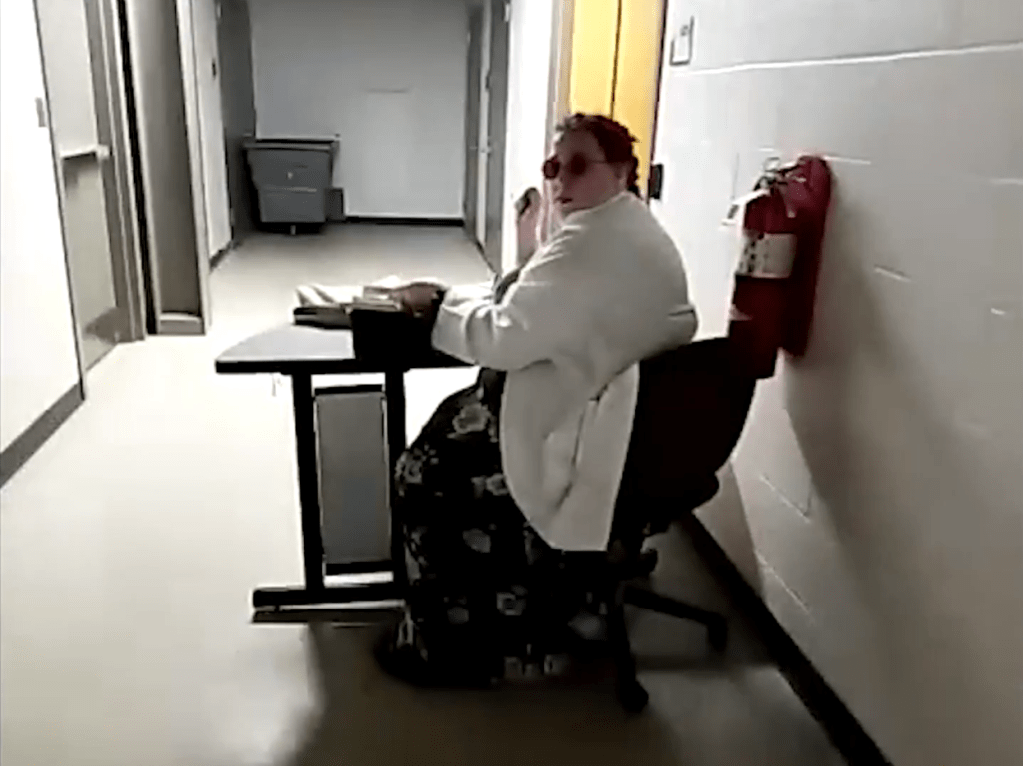

Figure 9. Pippin started as the TA, welcoming the FPV and introducing them

(and the Host and players) to the Memoirscape demo.

(Character creation and design by Shubham Sharma.)

Upon starting the official gameplay, the TA let us into the demo and then, ostensibly, stayed at her desk— but in reality, Pippin stayed behind me or to the side of the camera, directing me by a touch on the shoulder if necessary. She could hear Halina’s voice directing me (as the Host), so Pippin could also anticipate what I would need to do (though I often forgot and did things by hand myself— something that definitely would’ve benefited from more practice!).

While we both were familiar with the general flow of the gameplay for on-location players, we had to make some decisions on the fly as we learned how our remote players interacted with one another and the environment. For instance, following the discovery of a poor coming-out experience, the players started discussing among themselves the history of queer life (in the 1980s, in America), and providing context for the international players to understand the ramifications of the narrative.

This wasn’t something we wanted to interrupt, so we sat on the demo’s couch and left the camera’s view rest on a coffee table that happened to have a set of coasters that could be arranged to spell “YELLOWSTONE” (not a necessary clue to progress the narrative, but a sort of ambient clue to the overall solution). I gave Pippin the nod, and as my “hands” she started slowly solving the coaster puzzle while the players talked. She timed her solving along with the flow of the players’ discussion so that they didn’t feel pressured to stop talking in favor of moving forward; instead, the puzzle was ready for them to latch onto when the conversation came to a natural close.

Figure 10. The Yellowstone coaster puzzle, mid-solution,

solved by the AC while the players talked. (Prop created by Hannah Belan.)

Note that we broke visual continuity here, though; that’s Pippin’s right hand

coming from the left-side of the camera. With more practice/choreography,

that can probably be avoided.

While I didn’t have full access to the Zoom chat (and, in fact, sometimes notifications appeared that interrupted my camera view), a later look at the transcript showed that the chat function became a way for players who didn’t feel comfortable with speaking to still participate in the gameplay. (This was particularly noticeable during a text chain about the coaster puzzle that was happening in parallel to the out-loud discussion of the queer storyline.) It was extremely heartening to discover that even remote players could experience the multiple levels of interpersonal interaction that we previously thought might require being on-location.

Pippin stayed off camera but in costume as the TA throughout the demo room— if the players wanted to ask the TA a question, she would pass behind me while I turned around (the long way) to give her time to go back through the entrance door and return to the TA’s desk. Eventually, we left the demo room to find Professor Adler’s lab (at which point, the Admin puppet made its first appearance). When in the lab, Pippin only played my hands (see Figure 8, above); we did the same pass-and-turn trick when the players realized they needed to ask the TA for directions to the professor’s office.

The trickiest moment was after that— as soon as we got directions from the TA, I had to turn away from Pippin so she could take the elevator up one floor, dash to the office, and do a quick-change to become Professor Adler. Meanwhile, I went the opposite direction and took the emergency stairwell up, which required me to use my own hands to go through various doors (and also vamp a bit) to give Pippin as much time as possible to get set up. Again, due to the quick timeline, we were extremely fortunate that our building had a lot of doors, stairways, and elevators for us to take advantage of without having to come up with more complicated choreography.

Figure 11. Pippin as Professor Adler, lost among her stones. (Based on character performance by Maddie Veccia.)

Note that the overhead lights are on in this room; usually the lighting was provided by

small battery-powered tea lights and the ambient light of a flat-screen TV playing soothing screensavers.

We were unable to turn on the TV ahead of the playthrough, though, and were concerned that the light

provided by the tea lights would be insufficient for the camera (or me) to see some important clues in the room.

In the end, the overhead lights worked fine, but a lighting test probably would’ve been wise.

Pippin had to stay on-camera the entire time she was playing Professor Adler, so in the office I did have to shoot one-handed whenever I had to manipulate the (many) pieces of ephemera that closed the loop on the narrative and provided the final action required to complete the game. This came off a bit awkward, I think, but by this point the players were also so deeply invested that I think they were willing to forgive quite a lot to stay immersed in the story.

When the players wanted to return to the demo, I walked them back to the stairwell so that Pippin had time to change back into the TA, close the office, dash back to the elevator, and sit herself behind the TA’s desk before I arrived back at the entrance.

Figure 12. Pippin as the TA again, lounging with an exquisite sense of ennui.

She then let me back into the demo and we managed as we had the first time, with her letting herself out as soon as the players were ready to give their participant surveys to the TA and receive their compensation.

And that is how we did the remote run of an on-location immersive experience.

3. The End of the Line

Or what I’m calling the “if you’re only reading the call-out boxes I just really need you to know a couple more things” finale.

Final Tips and Tricks

- When you do your rehearsals with the camera, find “screensaver” positions where the FPV can sit, rest, and/or keep the camera pointed in one direction for a while to give the players a visual break.

- Screensaver positions can also be ones where the AC solves ambient puzzles or ones that require significant physical action (like playing a video game well enough to uncover a clue) while the players are discussing something else, but will probably need additional choreography to successfully maintain visual continuity.

- The FPV can’t use facial expressions to communicate with the players or the Host, but both they and the “hands” AC can use camera work and puppetry/clowning techniques to convey meaning and a nice bit of cinematic flair.

- Walking through the entire experience with the camera cage, smartphone, and a test Zoom is recommended: it checks the signal strength, the lighting levels, and potential tripping hazards.

- The Host needs to be strong and swift with the mute button, as accidental unmuted sound can break the immersion for other players and too many voices/directions can confuse the FVP.

- As we learned, introducing some kind of “help” mechanic (as the Admin was for Memoirscape) for the players and Host to call on remains important.

- The players didn’t mind the finger puppets, but when shorthanded a more professional/planned set of puppets would probaby be a good idea.

And that’s it! I mean, I should stress again that we were able to pull off a remote playthrough successfully and on very short notice because we had several lucky breaks: Halina already had experience with this kind of hosting; the players already had an established culture of Zoom/collaborative play etiquette amongst themselves, Halina, and me (which I can’t pretend didn’t smooth some of the rough spots); Pippin could pull emergency on-screen acting duties and had played the experience once already herself so she had character templates to work from; and, not neglecting her original AC duties, Pippin also had the foresight to pack a backup phone battery, which became abruptly necessary during certain important emotional revelations that would have been very unfortunate to leave on a dang cliffhanger.

But I think, at the very least, we can consider this a proof of concept– and hopefully what we learned from this one can help create better, more accessible remote play options in the future.

If you’d like to see TCF‘s remote playthrough yourself, you can find it here (Patreon membership is required to access it, but it’s about the same cost as a ticket would’ve been anyway). So far as I know, this is also the only full playthrough recording of the now-closed Memoirscape, so if you want to experience it again (or for the first time), it’s there and waiting for you.

Finally: If you’ve got questions, comments, or end up running your own remote playthrough and have some results to share, pop a comment below so others can benefit. Collaborative, creative community can work wonders, and I hope to see more of this sort of work toward inclusive gameplay in future.

Discover more from Katherine Crighton

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply